The Office of Head Start introduced data tours into federal monitoring several years ago to help programs articulate impact in a concrete and quantifiable way, according to Dr. Desiree Del-Zio, a former federal reviewer and current Director of Services at Early Intel.

Del-Zio offers the following example: During an FA2 review, a program leader might explain that as of last year, 90% of the families they serve were not signed up for WIC services, so they partnered with a hospital that could help fill this need. Now, every Wednesday, representatives from WIC visit their largest facility and help parents sign up. Thanks to this partnership, the number of families not signed up for WIC services has dropped to 20%. Having identified that language is one of the barriers for the remaining 20%, they plan to bring in representatives who speak Spanish or Mandarin and can help bring that number closer to zero.

Del-Zio’s example illustrates more than the ability to cite data. It illustrates a new mindset that emphasizes inquiry, the capacity for self-criticism and a commitment towards incremental improvement.

Compliance vs. improvement mindset

Head Start programs have historically operated under a compliance-driven mindset. For instance, if the benchmark was that 80% of children in the program meet or exceed expectations for outcomes in the Head Start learning framework, then program leaders would pat themselves on the back once they’d reach 80%. “They’d say, ‘wow, we are awesome,’” Del-Zio explains. “‘We met our 80%, so next year, we’re going to do 85%.’”

The trouble with that compliance-driven approach, she continues, is that “they think that moving the needle is all based on percentages and numbers, and they don’t really understand what components are in place that made those 80% successful and how can we leverage that to address whatever was missing over here with this 20%? They’re not disaggregating the data and analyzing it in such a way that they can articulate their opportunities for improvement.”

Gathering your Head Start data

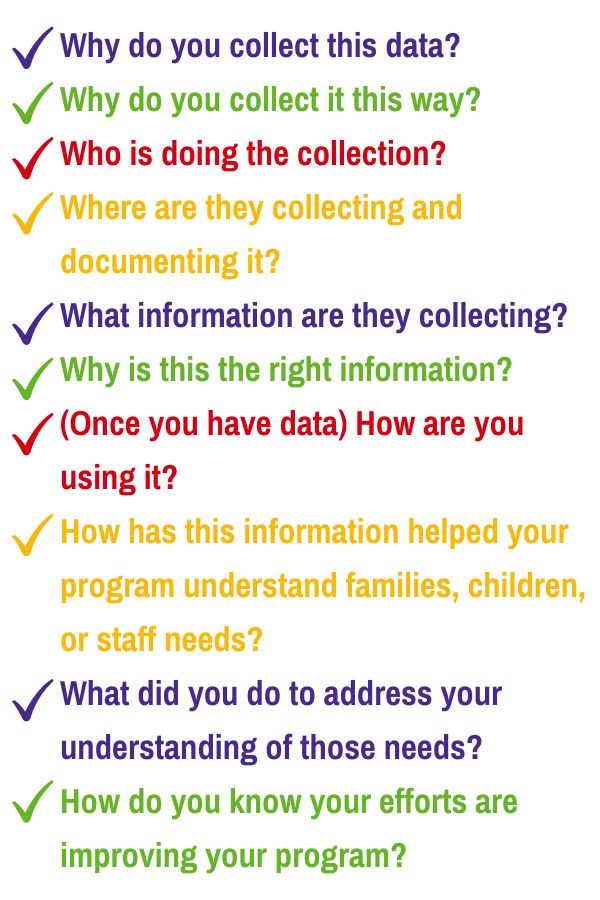

Simply reciting numbers doesn’t tell a compelling story. Meaningful and relevant data brings a narrative to life, so Del-Zio suggests thinking about questions like these:

Using Head Start data to highlight promising practices

By preparing data stories prior to a federal review, you can articulate specific examples of impact. For instance, perhaps you’ve reduced absenteeism through increased parent engagement and knowledge development, established innovative recruitment plans to boost enrollment, fully implemented a social-emotional curriculum to address family and staff well-being, or improved teacher retention through wellness programming.

“It’s addressed a problem, it’s changed the landscape so we can continue to track our outcomes while refocusing our efforts on other areas of programmatic need,” Del-Zio says.

Using Head Start data to understand shortfalls

Data stories can also help pinpoint and analyze areas for improvement. For instance, while early childhood programs typically excel in physical development, some struggle with teaching children to follow directions and cooperate with peers. “When it comes to some of those more cognitive approaches such as reasoning or self regulation associated with emotional growth, which are the biggest part of kindergarten readiness, they’re not meeting and exceeding those expectations,” Del-Zio says.

Realizing that the program needs to address social-emotional learning provides an opportunity for leaders to dig deeper and pinpoint potential root causes, whether it’s teacher motivation, staff knowledge, organizational culture, or something else entirely. Federal reviewers are likely to ask what’s causing a challenge, so proactive program leaders can dig into shortfalls and formulate improvements.

A program’s ability to articulate something like “our data indicated teachers’ motivation was impacted by increased behavioral challenges and their struggle to address these issues” is a great data story. An even better one adds how that motivational challenge was addressed. For instance, implementing reflective supervision with a mental health expert, providing additional classroom support, and establishing interdisciplinary planning committees are ways to address these challenges. When evaluated and measured, they can demonstrate quality improvement outcomes.

Next steps with your Head Start data

“The OHS is always very interested in the ‘so what?’ of all of this,” Del-Zio says. “You did all this great work, you did all of this analysis, you aggregated and analyzed data in such a way that you understood your opportunities and your risks.”

Programmatic or organizational improvements activities must be measured to demonstrate outcomes. Anecdotal data is fine but measured evaluation is better. In the example above using reflective supervision, classroom support, and interdisciplinary committees, program leaders can collect teacher and parent improvement survey responses, conduct focus group interviews, and review child outcomes data to determine if their strategies are working.

Ultimately, programs with effective data stories are committed to greater understanding and trying new ways to improve. But effective data storytelling requires practice–you don’t want to wait until your FA2 visit to master this new skill! We have seen, however, that programs that practice this skill will be rewarded with greater insight, better program outcomes, and a program culture of inquiry and improvement.